"God Ate My Homework": Worthwhile Temptations

On his arrival at Barcelona he told Isabel Roser and Master Ardevol, who was then teaching grammar, of his inclination to study. Both thought very well of it, Ardevol offering to teach him without charge, and Isabel to supply him with what was necessary for his support. In Manresa the pilgrim had known a friar, a Bernardine, I think, a very spiritual man. With him he wished to remain to make greater progress in the spiritual life and even to be of help to souls. He, therefore, answered that he would accept their offer if he did not find what he wanted in Manresa. But when he went there, he discovered the friar had died. Returning to Barcelona he began his studies with great diligence. But there was one thing that stood very much in his way, and that is that when he began to learn by heart, as has to be done in the beginning of grammar, he received new light on spiritual things and new delights. So strong were these delights that he could memorize nothing, nor could he get rid of them however much he tried.

Thinking this over at various times, he said to himself: “Even when I go to prayer or attend Mass these lights do not come to me so vividly.” Thus, step by step he came to recognize that it was a temptation. After making his meditation, he went to the Church of Santa Maria del Mar, near the house of his teacher, having asked him to have the kindness to hear him for a moment in the church. Seated there, the pilgrim gave his teacher a faithful account of what had taken place in his soul, and how little progress he had made until then for the reason already mentioned. And he made a promise to his master, with the words: “I promise you never to fail to attend your class these two years, as long as I can find bread and water for my support here in Barcelona.” He made this promise with such effect that he never again suffered from those temptations. The stomach pains which he had suffered in Manresa and were the cause of his taking to shoes, left him, and he felt well enough in that regard from the time he left Barcelona for Jerusalem. For this reason, while he was still at his studies in Barcelona, the desire returned of resuming his past penances, and he began by making a hole in the sole of his shoes, which widened little by little until by the time the cold of winter arrived, nothing remained of the shoes but the uppers.

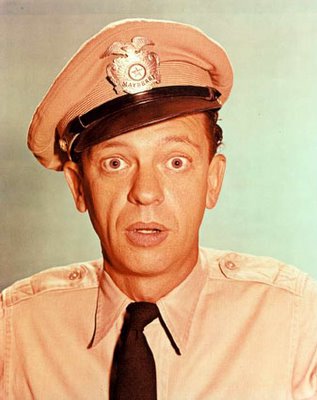

Here’s an excuse that’s way better than “the dog ate my homework”! Well, you see, I couldn’t get my homework done because of all the great spiritual insights I was receiving from God. Who could argue with that? But the question my students ask when I say “I know this happens to you all the time” is: If Ignatius is getting spiritual insight from God, how can that be a temptation? It’s a good question.

I guess what I can best relate it to is the writing process, as I don’t find myself frequently distracted by deep spiritual insights equal to Ignatius’. Often when you’re engaged in a writing project, like I am now, you suddenly discover you have all kinds of interesting insights coming to you about just about every subject except the one you are writing about! I know I’m supposed to be writing this book on the spiritual life, but suddenly all the ideas I need for my screenplay on the life of Saint What’s-Her-Name are just pouring into my brain. They are good insights, and they might even be coming from God somehow; but guess what, I have a deadline to meet on this other project! Maybe I can jot down a few notes for later, but right now such thoughts are a temptation, even if they’re not evil. This can be true of any worthwhile project that we are engaged in. Darn it, once we’ve made a commitment to it, it seems like there are all these pulls in other directions, not necessarily to bad things, just to distracting things.

Having recognized this, we might be inclined to ask another question at the end of this passage. Now that he feels better, Ignatius has decided to again take up some of his austerities, the result of which is that he has arrived at wintertime with no bottoms to his shoes! I wonder if it’s merely a coincidence that he is telling us this right after he’s recognized the previous temptation, or is he inviting us to ask the now obvious question: Is this a temptation too?